In a previous posting (read

here) I discussed the old rules relating to providing information about the funding of a claim. The latest update to the Civil Procedure Rules has made important amendments which came into force on 1

st October 2009.

The old CPR 44.3B read:

“(1) A party may not recover as an additional liability –

(c) any additional liability for any period in the proceedings during which he failed to provide information about a funding arrangement in accordance with a rule, practice direction or court order”

The new wording of CPR 44.3B is:

“(1) Unless the court orders otherwise, a party may not recover as an additional liability –

(c) any additional liability for any period during which that party failed to provide information about a funding arrangement in accordance with a rule, practice direction or court order;

…

(e) any insurance premium where that party has failed to provide information about the insurance policy in question by the time required by a rule, practice direction or court order.

(Paragraph 9.3 of the Practice Direction (Pre-Action Conduct) provides that a party must inform any other party as soon as possible about a funding arrangement entered into before the start of proceedings.)”

These changes fall into four categories:

1. The wording “in the proceedings” is deleted and the reference to the new wording of the Practice Direction (Pre Action Conduct) makes it clear that notice must now be given pre-proceedings.

2. The insurance premium provision deals with the consequence of not giving the information discussed below.

3. The addition of the new wording “unless the court orders otherwise” is perhaps surprising. It was previously clear that failure to comply with the notification provision produced an automatic sanction in that the additional liability was not recoverable (in the absence of a successful application for relief from sanctions). It now appears to be in the general discretion of the court as to whether to allow the additional liability despite the breach, although the starting point is obviously non-recoverability. What is strange is that the new wording is followed by the same note that previously appeared: “Rule 3.9 sets out the circumstances the court will consider on an application for relief from a sanction for failure to comply with any rule, practice direction or court order”. If the court now has a general discretion there would be no need to formally make an application for relief from sanctions. Or, is the wording “unless the court orders otherwise” meant to refer to the situation where a successful application has indeed been made, but not otherwise? We’ll no doubt have to wait for the first decisions on the correct interpretation.

4. The word “he” is replaced by the non-sexist “that party” (so as not to upset any chicks reading).

Paragraph 9.3 of the Practice Direction (Pre-Action Conduct) now reads (amendments underlined):

“Where a party enters into a funding arrangement within the meaning of rule 43.2(1)(k), that party must inform the other parties about this arrangement as soon as possible and in any event either within 7 days of entering into the funding arrangement concerned or, where a claimant enters into a funding arrangement before sending a letter before claim, in the letter before claim.”

For the reasons I gave in the previous posting on this subject, I am of the view that these changes clarify, rather than change, the requirements concerning pre-proceedings notification (although the corresponding transitional provisions might suggest the contrary).

An important change has been made to the Costs Practice Direction in respect of staged After-the-Event (ATE) premiums. CPD 19.4(3) now reads:

“Where the funding arrangement is an insurance policy, the party must –

(a) state the name and address of the insurer, the policy number and the date of the policy and identify the claim or claims to which it relates (including Part 20 claims if any);

(b) state the level of cover provided by the insurance; and

(c) state whether the insurance premiums are staged and, if so, the points at which an increased premium is payable.”

This finally formalises the guidance given by the Court of Appeal in

Rogers v Merthyr Tydfil CBC [2006] EWCA Civ 1134.

What is not 100% clear is what the consequence would be of failing to give notification of the fact the policy is staged or to give the trigger points. Would the receiving party lose all premiums or would they still be able to recover the first stage premium (on the basis that the paying party can be no worse off in respect of this first premium even if they were not notified of the staging; the prejudice comes from not having the opportunity to settle the claim before the subsequent premiums become payable)? More test litigation ahead for

costs draftsmen and other costs professionals.

It should be pointed out that none of these changes affect those acting under discounted CFAs\CCFAs without a success fee (usually defendants). There is no need to provide notice of funding in this situation because the full hourly rate payable in the event of a win is not treated as being an additional liability (see

Gloucestershire CC v Evans [2008] EWCA Civ 21).

There are also important changes to the rules concerning ATE premiums in publication proceedings although, frankly, if you work in that niche area you should already be more than aware of those changes.

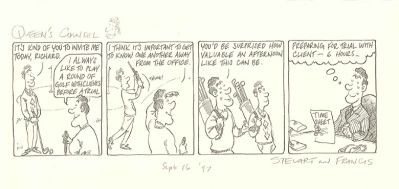

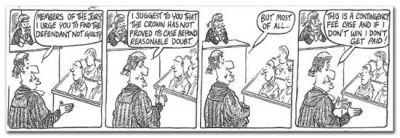

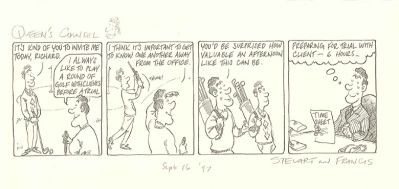

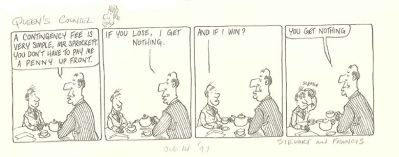

Click image to enlarge: