Arguably, Lord Justice Jackson’s most significant recommendation, in his Final Report, is an end to recovery between the parties of success fees.

This proposal will lead to obvious and huge savings to defendants. Those who think that current political uncertainty will lead to much of the Report being shelved should think again. Whichever party is in power after the general election, there will be a pressing need to control public expenditure. In terms of the money paid out by the NHSLA alone, and ignoring all the other areas where the public purse pays for litigation, this will be a compelling reason to adopt this recommendation. This is great news for defendants but really bad news for claimant lawyers.

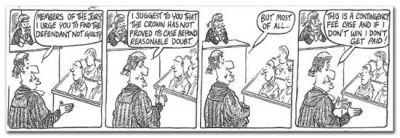

Yes, solicitors can still enter into CFAs with their clients and charge a success fee. But there are two big problems. Firstly:

(If you receive the Legal Costs Blog via email you made need to adjust your security settings to view the video.)

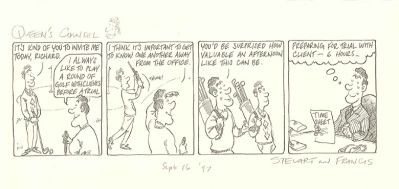

Heavy advertising in recent years telling potential claimants that they will keep 100% of their damages will make it very unattractive for claimant solicitors to now start taking a cut of their clients’ damages. There will be enough firms who decide to take the hit themselves that others will be forced to follow. Success fees in personal injury claims are likely to disappear. For the lower-end RTA claims, the loss of the 12.5% success fee will not be dramatic but it will come straight from solicitors’ profit margins. It is likely to discourage some claims from being pushed to trial where the incentive of the automatic 100% success fee will disappear. On the other hand, the removal of the 100% threat will encourage defendants to take more cases to court, especially in relation to quantum disputes.

Even if firms do feel able to charge success fees, Jackson LJ’s proposed cap will limit to a large extent the amount that can be charged. Not only is a cap of 25% of damages recommended, but Jackson LJ’s master-stroke is that this cap will exclude damages referable to future loss. The element of damages that claimants will be required to pay as success fee will be limited to the general damages and past losses. In heavy litigation, and in particular catastrophic injury and clinical negligence claims, the cap is going to bite significantly in a high proportion of claims. This will have a big impact on profit margins for some firms.

The claimant lobby has been arguing that this proposal will reduce access to justice. This argument fails for a number of reasons. These proposals largely revert the position to the one that existed prior to the Access to Justice Act 1999. As Jackson LJ happily notes: “During 1996 APIL confirmed that those arrangements provided access to justice for personal injury claimants and that those arrangements were satisfactory”. He further notes: “In this regard, it is significant that in Scotland personal injury cases are conducted satisfactorily on CFAs, despite the fact that success fees are not recoverable”. Until recently, most BTE work and trade union work was conducted on unwritten speccing arrangements. It is not obvious that recoverability of success fees brought about an increase in the kind of claim that was pursued. The same kind of claim will still be run but the profit margins will shrink.

The Jackson package, and in particular this recommendation, is designed, at least in relation to personal injury work, to reduce legal costs at the expense of claimant lawyers. And that can be no bad thing.