Monthly Archives: January 2009

Birmingham City Council v Forde

The recent decision in Birmingham City Council v Forde [2009] EWHC 12 (QB) is a worrying one both for Defendants and for the legal profession generally. This was an appeal to the High Court from a decision of the Supreme Court Costs Office. Unusually, for a case heard in Birmingham District Registry, the Senior Costs Judge Master Hurst sat with the Judge as one of the assessors. The judgment is long and detailed but we will try to summarise the important issues.

The Claimant’s solicitors had entered into a Conditional Fee Agreement (CFA) with the Claimant which did not include a success fee. The CFA was entered into prior to the revocation of the CFA Regulations 2000. Shortly before the conclusion of the claim, the Claimant’s solicitors became concerned as to the validity of their CFA due to challenges that the Defendant local authority had been raising in relation to similar agreements. They therefore entered into a second CFA that purported to cover all work performed, including the work already done under the original CFA. This new CFA sought a success fee of up to 100% if the matter proceeded to trial. The new CFA was entered into after the revocation of the CFA Regulations 2000. A letter was sent to the Claimant together with the CFA which stated that all legal costs to date were to be dealt with under the second agreement unless the Court ruled that the new agreement was invalid, in which case the original CFA would be relied on. The Defendant challenged the validity of the second CFA. On appeal it was held:

• Following Jones v Wrexham Borough Council [2007] EWCA Civ 1356, it was confirmed that the letter formed part of the second CFA.

• There was nothing wrong with seeking to rely on the first CFA in the event that the Court held the second to be invalid.

• There was adequate consideration for the second CFA by virtue of the agreement to continue to act for the Claimant. This was particularly so given the doubt over the validity of the first CFA. The obligation to provide services under the second CFA in place of a potentially unenforceable obligation under the first CFA was consideration for a fresh promise to pay.

• It was permissible, as a matter of general principle, for a CFA to be retrospective (confirming Master Hurst’s decision in King v Telegraph Group Ltd [2005] EWHC 90015 (Costs)).

• It was not, per se, contrary to public policy to allow a retrospective success fee. This contrasted with Master Hurst’s view in King. A court was held to have sufficient power to reduce or disallow success fees that were unreasonable.

• The Judge held that even if he was wrong as to whether it was contrary to public policy to allow a retrospective success fee, it did not follow that the second CFA was invalid. He could “see no reason why the Court cannot place its blue pencil through the success fee provision”.

• Given the above, the second CFA was held to be valid. The Claimant had abandoned any claim for a success fee and the Court therefore did not have to decide what success fee, if any, it would have allowed.

This decision throws up a number of concerns:

• The notion that a solicitor can have a number of “belt and braces” arrangements in place and be able to rely on one if others fail is an uncomfortable proposition. It has generally been accepted that there can be only one retainer in place at any one time in relation to the same matter. This decision would appear to invite solicitors to enter into novel retainers at or beyond the very borderline of enforceability with a second, safer, agreement to fall back on in the event that the other is held to be defective.

• The judge ruled:

“It is material to note that the occasions when a retrospective CFA will be entered into after a CFA without a success fee has already been signed are likely to be limited. If such a CFA already exists the solicitor will be bound by it and is unlikely to need, or be able, to enter into a new retrospective CFA. In the present case it is the fact that the Council challenged the validity of [the first] that provided both the incentive for a new agreement and its justification.”

What is this meant to mean in practice? What does it mean when the Judge says a solicitor would not be “able” to enter into a new retrospective CFA? Would the CFA be defective in that situation and all costs be disallowed? Would the “blue pencil” approach rescue the CFA as a whole but simply strike down the success fee? What if the solicitors were concerned as to the validity of their CFA but no actual challenge had yet been raised by the Defendant, unlike in this matter? In what other circumstances would a solicitor be “able” to enter into a new agreement? This decision raises more questions than it answers.

• The decision that there was nothing wrong with a retrospective success fee in principle is perhaps the most worrying aspect of this judgment. The whole ethos of CFAs is that the solicitor accepts the risk of non-payment of future costs at the time of entering into the agreement and that when it comes to assessing the reasonableness of a success fee the Court will “have regard to the facts and circumstances as they reasonably appeared to the solicitor or counsel when the funding arrangement was entered into”. The Court is not meant to use the benefit of hindsight. This issue was explored by the Court of Appeal in KU v Liverpool City Council [2005] EWCA Civ 475, where it was determined that a Court did not have the power to award different success fees for different periods in a claim where the CFA itself did not provide for the same:

“The approach of the district judge negates the whole purpose of assessing at the outset the risks involved in pursuing a claim. The solicitor did not have the contractual power or the professional duty to do what the district judge suggested, namely to renegotiate the success fee once it became clear that the risks were now very small and that there was no longer any need to fear a ‘worst case scenario’ such as might have been in the solicitor’s mind when the CFA was initially agreed.”

The decision in Forde appears to give Claimant solicitors the right to enter into a retrospective CFA with a success fee, or amend the success fee of an existing CFA retrospectively, with the benefit of hindsight. However, given the clear Court of Appeal decisions on the subject, the Court does not have the power to reduce a success fee applying the benefit of hindsight. Given it can be safely assumed that Claimant solicitors will not voluntarily reduce their success fees if a case becomes less risky, the outcome will inevitably be higher success fees paid by defendants. If a solicitor, for example, set a success fee at 40% for a case that carried some real risks, and 40% was an appropriate figure at that stage, the Court has no power to allow a different success fee at any point in the claim simply because the case becomes much more straightforward at a later point, even if liability is admitted the following day. However, the decision in Forde appears to allow the solicitors to increase the success fee, and potentially recover an increased amount, if the claim becomes more complex. This undermines the whole principle on which CFAs were meant to be based.

• The judgment also ignores the views expressed by Lord Hoffman in Callery v Gray [2002] UKHL 28 as to whether a CFA could be retrospective under the current rules and also the policy issues that were argued in that case. It will be recalled that the Defendants in Callery argued that it was unreasonable to enter into a CFA from the outset and that this should be delayed until a response had been received from the Defendant. Lord Hoffman commented:

“22. Three arguments were given for fixing the success fee at once. The first was that it was a necessary part of a conditional fee agreement and that it was natural for client and solicitors to want to agree at the first opportunity upon the terms of engagement. The client wants to be sure from the beginning that whatever happened he will not have to pay any costs and the solicitor wants to be sure that any work he did will be covered by the agreement and recoverable (in the event of success) from the defendant. The Court of Appeal recorded (at p 2132, para 90) the claimants’ argument:

“The claimant will be concerned [when he first instructs a solicitor] that, by giving instructions…he is not exposing himself to liability for costs. The solicitor for his part will be anxious to offer the claimant services on terms that, whatever the outcome, he will not find himself liable for costs.”

23. I am sure that giving such an assurance is an important selling point… and perhaps under the present rules an immediate conditional fee agreement is the only practical way of achieving it [emphasis added]. In a large-scale study undertaken in 1998 on behalf of the Legal Aid Board Research Unit (Report of the Case Profiling Study Personal Injury Litigation in Practice) Mr Pascoe Pleasence noted (at p. 19) that “it was common for clients to have their initial advice in a free consultation with a solicitor. Often firms used free first consultations as a marketing tool…”. It may therefore be that if a solicitor had to wait until he received an answer to his letter before action before fixing the success fee, he would be willing for marketing purposes to take the risk of not being able to recover from anyone the relatively trivial costs already incurred. On the other hand, it may need a change to the indemnity principle to provide him with the additional incentive of being able to recover those costs from the defendant if the claim succeeds [emphasis added]. These are empirical questions on which it is difficult for judges to form a view.

24. The second argument was that by agreeing to a success fee at the first meeting, the client so to speak insures himself against having to pay a higher one later if his case turns out to be more difficult than at first appeared. … At first sight, therefore, one could say that agreeing an immediate success fee is no more than economically rational behaviour on the part of any client and that the fee should therefore be recoverable as an expense reasonably incurred.”

If it is now being suggested that there is nothing wrong in having retrospective CFAs and retrospective success fees then the whole issue of timing needs to be urgently re-examined. The justification for entering into CFAs at the outset, that was argued for in Callery, disappears if Forde is correct. Further, it cannot be right that this only operates in favour of claimant solicitors who can move success fees upwards if a case becomes more risky but there be no duty on the solicitors, or power of the courts, to lower success fees if a case becomes more simple. Just as some certainty was beginning to enter this difficult area the whole issue appears to be unravelling.

• An unfortunate element of this judgment is how little consideration appears to have been given to the issue of whether there were public policy objections to allowing the second CFA to replace the potentially defective first CFA. The judge seems to have gone no further than considering that there was no inherent objection to a retrospective CFA. This is unfortunate because, we would suggest, there is very clear guidance on the correct public policy approach. When the CFA Regulations 2000 were revoked, such revocation could have been made retrospective so that failure to have complied with the Regulations in a material manner would no longer have the consequence that a pre-November CFA agreement was invalid. However, a decision was clearly taken not to adopt this approach. Indeed, the CFA (Revocation) Regulations 2005 expressly stated that the Regulations would continue to apply to CFAs entered into before 1st November 2005. One of the main reasons why the Regulations were revoked was because of the perceived unfairness in a solicitor losing all their costs as a result of what might be viewed as a mere technical breach. Nevertheless, the decision not to make the revocation retrospective must have been taken with full knowledge and intention that solicitors would not recover costs if a breach had occurred pre-1st November 2005. Further, the Court of Appeal has shown itself willing to find older CFAs invalid since the revocation. Given this, it should be clear that there is already a clear public policy as to the consequences of failing to comply with the Regulations for cases where the Regulations were still in force: non-recovery of costs. The apparent total failure in this judgment to consider whether it could therefore be legitimate to use the device of a retrospective CFA to recover costs that might otherwise be irrecoverable is therefore unfortunate.

A further issue that the judgment considered was the extent to which there is or is not a duty to advise a defendant of the existence of a CFA with a success fee before proceedings are issued. This issue was of particular importance here given notification could obviously not be given of a CFA until the same is entered into. Could it be right for a success fee to be claimed for a period in the claim where a defendant had no knowledge that a CFA was in place (or was to be put in place)? This was one of the factors that persuaded Master Hurst in King that a retrospective success fee could not be recovered. The question of whether there is a duty to notify pre-proceedings is something of a grey area with various conflicting decisions. The judge in Forde appeared to accept that there was no duty to give such notification. However, given the Claimant had withdrawn the claim for a success fee, these observations can probably be treated as being obiter only.

This case might be viewed as simply a pragmatic attempt to allow for a retrospective CFA to replace a potentially invalid one and therefore avoid the perceived injustice of the solicitors losing all their costs. Unfortunately, the decision opens a can of worms that applies with equal force to agreements entered into under post-revocation of the CFA 2000 Regulations.

C v W

The recent Court of Appeal decision in C v W [2008] EWCA Civ 1459 was concerned with a CFA with a success fee that was entered into after liability had been admitted by the Defendant’s insurers. This judgment, in many respects, follows the earlier decision of Haines v Sarner [2005] EWHC 90009 (Costs), in which Simon Gibbs acted for the Defendant. In relation to Part 36 offers, CFAs normally contain one of the following two clauses:

‘It may be that your opponent makes a Part 36 offer or payment which you reject on our advice, and your claim for damages goes ahead to trial where you recover damages that are less than that offer or payment. If this happens, we will not add our success fee to the basic charges [emphasis added] for the work done after we received notice of the offer or payment.’

or

‘It may be that your opponent makes a Part 36 offer or payment which you reject on our advice, and your claim for damages goes ahead to trial where you recover damages that are less than that offer or payment. If this happens, we will not claim any costs [emphasis added] for the work done after we received notice of the offer or payment.’

The CFA in C v W contained a variation similar to the second clause. The distinction between these two clauses is crucial. The first one does not put the solicitor at risk in relation to Part 36 offers – they will still be paid their base costs. The second clause does, as failure to beat a Part 36 offer will mean the solicitor recovers nothing from that point onwards.

The judge at first instance allowed a 70% success fee. At the initial appeal this was reduced to 50% but the Defendant appealed again on the basis that the amount was still too high. The Court of Appeal held:

• “In the absence of any evidence that the accident had been caused by anything other than negligence on the part of the driver and in the light of the fact that his insurers had already admitted liability on his behalf, it is difficult to see how Mrs. C could have failed to recover substantial damages given the serious nature of her injuries. Mr. Post submitted that the defendant might have applied to withdraw the admission and contest liability, but that was little more than a theoretical possibility in the absence of some evidence to suggest that the accident occurred without any fault on his part. It follows that the chance of success in this case was very high and the risk of losing correspondingly low – certainly no more than 5% and probably rather less. Applying the ready-reckoner, that would give a basic success fee of at most 5% rather than the 33% calculated by Taylor Vinters.”

• It was wrong to add a further 20% success fee to reflect the size of the claim. “It is probably true in general that high value claims tend to be more complex and to involve a greater amount of work than claims of lower value, but that does not of itself increase the risk of losing. If more work is done the base fees are inevitably higher, but the application of a percentage success fee means that the amount recovered by the solicitor if the claim succeeds is correspondingly greater.”

• The main issue in this case related to the risk of failing to recover part of the solicitors’ fees because of the Part 36 clause. “Given that the CFA was entered into before proceedings had been commenced, that called for an analysis of several contingencies, each of which was difficult to assess individually, and which together made the task almost impossible. They included the chance that a Part 36 offer would be made, the chances that it would be made at an earlier or later stage in the proceedings, the chance that they would advise Mrs. C to reject it, the chance that she would accept their advice and the chance that, having rejected the offer, she would fail to beat it at trial. … The timing of an offer was … potentially of some importance because only fees earned by the solicitors after its rejection would be at risk; fees earned up to that point would be secure. … The task facing Taylor Vinters in May 2001 was to assess, as best they could, the risk of losing part of their fees for reasons of that kind, and then expressing that as a percentage of the total fees likely to be earned to trial.”

• It was wrong to allow a further success fee element to reflect the risk the Claimant might not pursue her case. If that had happened, the solicitors, under the terms of the CFA, would be entitled to look to the Claimant for payment in any event. The solvency of the Claimant was not a factor that the success fee was designed to cover.

• Although calculating the real risk in a case such as this was a difficult task, it did not follow that it was unreasonable to enter into a CFA in this situation.

• “However, given that the risks associated with [the Part 36 clause] are so difficult to assess, it would, perhaps, be worth considering whether it would make sense for solicitors who wish to offer it to include in the CFA a variant of the two-stage success fee discussed in Callery v Gray [2001] EWCA Civ 1117, in the form of a clause giving them the right to review the success fee once an offer to which the clause applies has been made. Both parties would be sufficiently protected against an excessive increase by the right to require a detailed assessment.” In what is otherwise a very carefully considered judgment this is the one worrying aspect. It appears to raise a number of the potential problems identified above in relation to Forde. It is to be hoped that this passage is actually to be interpreted as suggesting a “break clause” in CFAs. An initial success fee would apply to deal with the claim up until the stage liability is resolved. At that point, what is in reality closer to being a second CFA with a different success is agreed that reflects the Part 36 risks at that point. This would be entirely sensible and fair to all parties.

What the judgment almost touched on, but did not actually consider, is whether it is ever permissible to enter into a CFA that does not include a clause putting the solicitors/counsel at risk in relation to Part 36 offers where there has already been judgment on liability entered for the Claimant. Where an admission is made pre-proceedings then it probably is reasonable to have a CFA with a small success fee to reflect the, at least “theoretical”, possibility it might be withdrawn. Lord Justice Moore-Bick, in the leading judgment, stated:

“…I should make it clear that there is nothing unreasonable in my view in entering into a simple CFA at a time when liability has been admitted provided that the parties make a proper assessment of the inevitably much reduced risk of failure.”

What does “simple CFA” mean? Is it meant to refer to one that contains one or other of the Part 36 risk clauses identified above? If the CFA does not contain a clause putting the solicitors/counsel at risk on Part 36 offers, and judgment on liability has already been achieved, what is the risk to the legal representative? They have already achieved a “win” as defined under the terms of a standard CFA and would be entitled to payment of their base costs. Is such an agreement in this situation even lawful? In Arkin v Borchard Lines Ltd [2001] NLJR 970 Coleman J held:

“On the proper construction of [section 58] the only permissible conditional fee agreements are those entered into before it is known whether the condition of success has been satisfied. The provision in section 58(1) that:

‘In this section a ‘conditional fee agreement’ means an agreement in writing between a person providing advocacy or litigation services and his client which – (b) provides for that person’s fees and expenses, or any part of them, to be payable only in specified circumstances’

clearly referred to circumstances which have not eventuated at the time when the agreement is entered into. The legislative purpose of the legalisation of such agreements was to enable those who could not afford to employ the legal profession to present their case on the basis that their obligation for fees and legal charges by their solicitors and counsel would arise only if the proceedings which were yet to be heard had been successfully prosecuted. It was no part of the purpose of the legislation to provide for agreements to pay fees and expenses which were entered into after the successful conduct of the proceedings.”

On this analysis there is a strong argument that a CFA in this situation would be unlawful. In fact, it is quite common to see just such agreements entered into after judgment has been entered. This is particularly so in the case of counsel becoming involved at a later stage of the claim. It appears that counsel routinely enter into CFAs with large success fees without any proper consideration as to what risk they are purporting to accept. The issue of whether this type of agreement is lawful arises regardless of whether the CFA post-dates the revocation of CFA Regulations 2000 or whether the case is of a type which would otherwise attract a fixed success fee.

The alternate view is that despite purporting to be a CFA, it is not possible to enter into such an arrangement where payment of no part of the fees is actually conditional. Therefore, although such an agreement would not be unlawful, it would not be possible to recover a success fee.

GWS have a number of cases where this is a live issue and we will report any relevant decisions in due course.

Claims Handling Law and Practice – Book Launch

GWS partner Simon Gibbs has contributed two chapters on legal costs to the recently published Claims Handling Law and Practice – A Practitioner’s Guide. Produced, and otherwise written, by leading defendant solicitors Kennedys, this practitioner’s desktop handbook is an invaluable tool for claims handlers. It covers all areas of general liability including motor claims, clinical negligence, health & safety, disease, abuse and housing disrepair. The previous edition of this book proved extremely popular (see link: Amazon review) and this new fully updated edition is sure to be similarly successful. For ordering details use this link: Publishers.

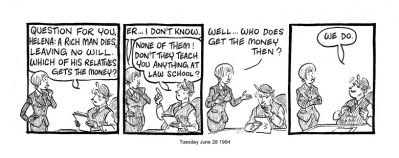

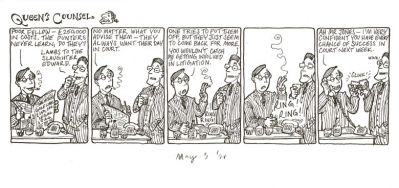

Queen’s Counsel

Part 47.19 Trap

CPR 47.19 allows a party to make an offer to settle the costs of proceedings. The corresponding Costs Practice Direction states that, unless the offer states otherwise, the offer will be treated as being inclusive of the cost of preparation of the bill, interest and VAT. It might therefore be assumed that if a Part 47.19 offer is made and accepted that will conclude matters. Unfortunately not.

The Court of Appeal’s decision in Crosbie v Munroe [2003] EWCA Civ 350 makes it clear that a Part 47.19 offer does not include the costs of the detailed assessment proceedings (ie the work relating to negotiations and assessment of the costs of the substantive claim). Therefore, acceptance of a Part 47.19 offer, even if the offer is expressed to be “fully inclusive”, would not conclude matters. It leaves open the possibility of the other side returning to seek further payment in respect of the assessment costs. This is a trap for the unwary.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that there is no automatic entitlement on the part of the receiving party to their assessment costs even upon acceptance of a Part 47.19 offer. There is a general presumption, but no more, that the receiving party is entitled to the costs of assessment (CPR 47.18(1)). When deciding which party to award these costs to, the Court must consider the factors listed in CPR 47.18(2) including CPR 47.18(2)(b) which is the amount by which the bill has been reduced. The danger, of course, is that despite reaching agreement on the substantive costs, one then has to proceed to assessment in relation to who should be entitled to the assessment costs.

The way to deal with this problem is to make clear in any offer that it is inclusive of the costs of the detailed assessment proceedings. Although this may technically mean the offer is no longer a Part 47.19 offer, the basis of the offer is clear and we have never experienced any problems at court with this approach.

Queen’s Counsel

Click image to enlarge: