At the end of July I attended the last of Jackson LJ’s Costs Review Seminars. This seminar focused on detailed assessments and explored various ways to try to improve the process. The majority of those attending were costs draftsmen, costs judges and other costs professionals.

What was interesting was the way that some of the ideas that emerged were met with virtually unanimous support from those present except for one or two individuals who clearly passionately believed that these very same proposals were either unworkable or entirely counter-productive.

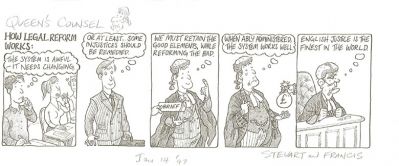

One of the suggestions was that the current format for bills of costs was inappropriate and should be replaced with a new format. Rather than, as now, largely focusing on a list of chronological items of work, the bill should be more focused on providing an explanation as to why certain work was necessary or why this work was unusually time consuming. This proposal received virtually unanimous support and a costs judge and a regional costs judge have been tasked with producing a new model bill to incorporate this suggestion.

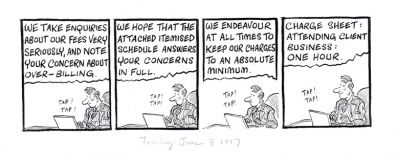

Although understanding the logic behind this proposal, I was one of the very few who strongly opposed this idea. Preambles to bills are already often unnecessarily long and self-serving, trying to justify the level of costs claimed by highlighting the supposed difficulties in the matter. My concern is that any formal requirement to explain and justify at the outset the costs claimed will turn bills into pages of lengthy prose that serve little purpose other than to drive up costs. Worse, much of this may prove to be entirely wasted. Time will be spent seeking to justify work that the paying party may have had no intention of disputing. Hopefully the model bill and any changes to the rules will overcome my concerns.

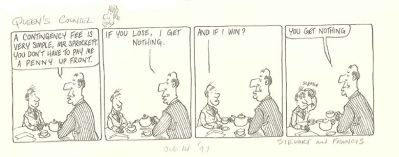

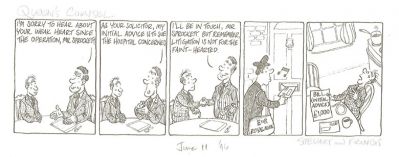

A second proposal was to introduce provisional assessments for lower value claims for costs. These would be conducted on paper with an option to proceed to a full detailed assessment if a party was unhappy with the provisional assessment, though possibly with strict costs penalties if a party failed to do better at the full assessment. I shared the majority view that this was a sensible proposal. There were only two dissenters and these were, interestingly enough, a regional costs judge and a costs officer. Their concern was that the provisional assessment option would be so attractive to parties that it would lead to a far higher number of cases reaching the courts than currently proceed to detailed assessment. This would lead to the courts being swamped with work they could not cope with. Of course, given any proposals emerging from the Jackson Review will almost certainly include fixed costs for fast-track claims this concern may be somewhat misplaced. Based on the figures being discussed at the seminar, for cases to be eligible for provisional assessment, most multi-track claims would be excluded. There would be relatively few claims likely to qualify once fast-track claims are removed from the process. Further, the workload of the courts should significantly decrease, in terms of costs disputes, as a result of fixed costs.

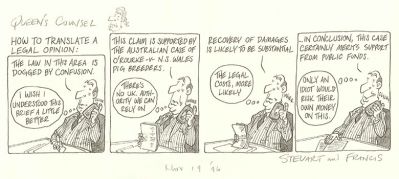

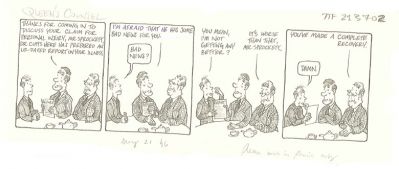

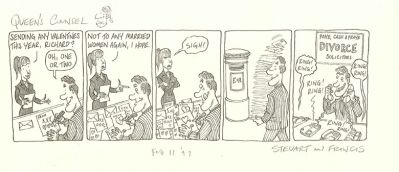

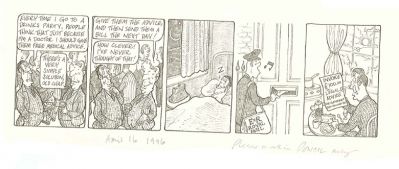

Click image to enlarge: